At 7:20 AM, the smell of freshly baked muffins greets us at Cowpuccino’s, the sole coffee shop in town. A makeshift directional sign points to Rome 5431 miles to the east and to Tokyo 4428 miles to the west. Another marker on the pole shows the Alaska border is now 26 miles north. We’re in the land of the “Mounties” — the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

One of my favorite movies as a child was “Susannah of the Mounties” with Shirley Temple. Shirley, the orphaned survivor of an Indian attack in the Canadian West, is rescued by a handsome Canadian Mountie and his plucky girlfriend. True to the predictable plot of all her films, little heroine Shirley saves the day by charming the tribe’s Chief into a peace treaty with the settlers. The real hardships of early pioneers in this corner of the continent were not so easily overcome.

Established in 1873, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) have jurisdiction as peace officers in all provinces and territories of Canada. In addition, the service provides police services under contract to eight of Canada’s provinces (except Ontario and Quebec), all three of Canada’s territories, more than 150 municipalities, and 600 Indigenous communities. The RCMP is also responsible for border control, and we have filed our Port of Entry paperwork with the local harbormaster.

Sunbreaks illuminate the ridge tops as we gently pull away from the dock and head south past Lelu Island, an old Chinook name for “wolf.” In fact, coastal wolves inhabit many of these islands. Unlike mainland wolves that hunt abundant deer, mountain goats, and moose in the forests of British Columbia and Alaska, coastal wolves swim between the islands in search of spawning salmon, harbor seals, and sea otters.

My friend interrupts my reverie to point out the Lawyer Islands ahead to port, bordered by Client Reefs and Bribery Islet. We wonder about who might have named them and the story behind the humorous names.

For the next hour, the water is flat calm as we pass a dozen more small, forested islands and outcroppings along Arthur Passage—verdant green stands of pine with no houses, no telephone poles, no cell towers.

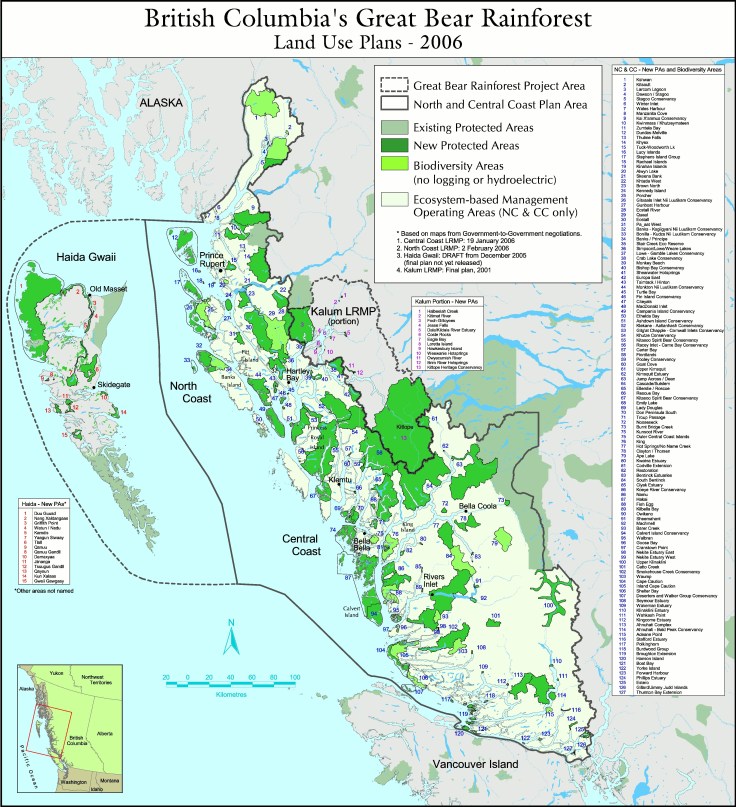

We are in the heart of the Great Bear Rainforest, roughly 16 million acres, one of the largest remaining tracts of unspoiled temperate rainforest left in the world. The area is home to grizzly bears, cougars, wolves, salmon, and the Kermode or “spirit bear,” a unique subspecies of black bear. One in ten cubs displays a recessive, white-colored coat!

The forest features 1,000-year-old Western red cedar and 300-foot-high Sitka spruce. Coastal temperate rainforests are characterized by their proximity to both ocean and mountains. Abundant rainfall results when the atmospheric flow of moist air off the ocean collides with mountain ranges. In 2016, the Canadian government agreed to permanently protect 85-percent of this primordial forest from logging. On the western coast of Vancouver Island is another protected rainforest—the Pacific Rim National Reserve near Tofino. We had hiked the trails there when our son was only eight years old. When we lived in Sequim, we often trekked the moss-laden rainforest trails in the Olympic National Park. And I wonder–why is it so difficult to protect 100-percent of these fragile ecosystems?

According to our chart, the large island to our starboard side in Grenville Channel was named after William Pitt by Captain George Vancouver during his explorations in 1793. Pitt was only 24 in 1793 when he became Prime Minister of Great Britain, a post he would hold intermittently for the next 20 years (he’s still the youngest PM in Britain’s history). Of course, Fort Pitt and my hometown of Pittsburgh were also named after this man who died when he was just 47. Perhaps as unfathomable for Pitt to imagine dozens of places in the New World named in his honor, as it was for a small girl from Pittsburgh to imagine sailing these pristine waters on a private yacht.

Described by a coast pilot account written in 1891: “In Grenville Channel, the land on both sides is high, varying from 1500 to 3500 feet and as a rule densely wooded with pine and cedar. The mountains rise almost perpendicular from the water and cause the southern portion of this narrow channel to appear even narrower than it is. But the general effect of so many mountains rising one behind the other renders the Grenville Channel one of the most beautiful landscapes in these waters.”

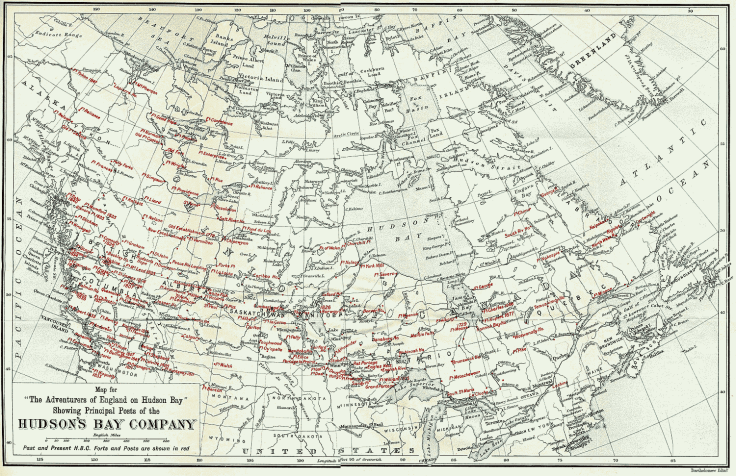

As we pass Stuart Anchorage, I seem surrounded by history I’ve researched and written about in magazine articles. Captain Charles Edward Stuart was the last Commander in charge of the Hudson Bay Company’s trading post at Nanaimo before it closed in 1859. Some seventy years earlier, Captain James Cook on his third voyage of discovery along the coast of British Columbia traded a few muskets for thick beaver pelts. Although Cook was murdered by islanders when his ship wintered in the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), those beaver furs would create a sensation once his ship the Resolution arrived in Peking harbor. A few lush beaver pelts from the forests of Vancouver Island would spawn the Silk Road trade route, the Hudson Bay Company, John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company, the explorations of Lewis & Clark in search of an inland route for spices and silks from China, and the early settlement of the Pacific Northwest.

Sadly, today you will not find beavers in the forests along this fjord – a natural resource trapped to extinction. The fur trappers were followed by loggers who also plundered the riches in this part of the world. Thick stands of cedar and fir trees that carpet the mountainsides in all directions are largely second growth—many majestic and irreplaceable old growth Western red cedars and Sitka spruce along this coast disappeared more than 150 years ago.

We have been traveling in awe through this still wild place, the forested hillsides interspersed by waterfalls that cascade down from high mountain lakes. We’ve not seen any sign of man, no cabins, no settlements and only two boats in the last four hours. A landscape where one can still breathe deeply.

We skirt Princess Royal Island along the Fraser Reach, named after Donald Fraser, a native of Scotland and businessman in Victoria in the 1860s. Fraser promoted steamers through the isthmus of Panama as a faster way between the British colony and Europe than the arduous journey around Cape Horn and South America.

Captain Vancouver anchored his ship Discovery near these islands in June 1793. He recorded that the weather was foul and the fishing terrible.

Our weather is also overcast and cold as we search for anchorage for the night at an abandoned cannery near Butedale Falls. When we arrive, it’s raining hard, and the small floating dock is already crowded. Chris determines it’s too deep to anchor so we continue south past the iconic Boat Bluff Lighthouse on Sarah Island.

Originally established in 1907, the Boat Bluff Lighthouse was built during the fifth phase of lighthouse construction on British Columbia’s coast. Lightkeepers are the only residents of the island, and the picturesque station is a well-known landmark to vessels which must pass closely in order to navigate the very narrow Tolmie Channel.

Both Sarah Island and nearby Jane Island were named after the daughters of John Work (nee John Wark in County Donegal, Ireland), an officer of the Hudson Bay Company (HBC) instrumental in the expansion of the fur trade and establishment of HBC outposts in the Northwest.

Work who had 10 children began a series of 15 remarkably observant and informative journals of his field trips in the Pacific Northwest from July 1823 to October 1835. Crossing inland from Calgary via the Athabasca River and Athabasca Pass, the party reached the HBC Boat Encampment at the big bend of the Columbia River. This was the major fur trade route from the interior of British Columbia and the areas around present-day Banff and Jasper National Parks. He helped extend the river trade into the Flathead country in Montana and later traveled with colony Governor George Simpson to the headquarters of the HBC district at Fort George in Astoria, Oregon.

Work also accompanied an expedition under Chief Trader James McMillan sent by Governor Simpson to explore the lower reaches of the Fraser River for the purpose of locating a site for a major post. Simpson was convinced the British could not retain control of the south bank of the Columbia River. On the return trip in December 1824, McMillan and Work discovered the Cowlitz Portage, which became an important link between the Columbia River and Puget Sound. In the spring of 1825, Work helped move the headquarters from Fort George to the newly established Fort Vancouver on the north side of the river (now in Washington State).

Governor Simpson then assigned Work as head of Spokane House with instructions to establish a new and better located post on the Columbia at Kettle Falls which became Fort Colville. Work took pride in the success of the Fort’s farm which helped to make the district independent of expensive imported provisions. He also conducted trading expeditions and procured horses along the Snake River for the company’s brigades at New Caledonia (British Columbia) and Fort Vancouver. Work often accompanied the fur returns from New Caledonia and his own district to the lower Columbia River to Astoria where they would be loaded onto steamers bound for China.

In August 1830, Work became Peter Skene Ogden’s successor in charge of the Snake Country brigade. Between August 1830 and July 1831, he travelled some 2,000 miles into what is now eastern Idaho, northwestern Utah, and the Humboldt River in Nevada. The returns of the expedition were profitable but still disappointing. Work went into the Salmon River (Idaho) and Flathead country in 1831–32. The rugged terrain and marauding Blackfeet made the expedition difficult, and the returns were not great, partly because of growing competition from the Americans. In his report for 1832, Governor Simpson recommended that the Hudson Bay Company withdraw from the Snake Country.

In September 1832, Work was assigned to the Bonaventura Valley (Sacramento) in Mexican California. Trapping in the valley was not favorable because of established American trappers and Native American hostilities, forcing Work and Laframboise to join forces in an exploration of the coast from San Francisco to Cape Mendocino. Disappointed in the hunt (an estimated 1023 beaver and otter skins), Work returned to Fort Vancouver in October 1833.

In December 1834, Work succeeded Ogden in charge of the coast trade at Fort Simpson, B.C. on McLoughlin Bay. He sailed north on the HBC brig Lama and supervised the construction of Fort Simpson. He also traded along the northern coast of New Caledonia, on northern Vancouver Island, and the Queen Charlotte Islands, always with keen competition from American coastal traders.

In January 1836 he was back in Fort Simpson, his permanent residence for the next decade. In his journal, he wrote that the natives were “numerous, treacherous . . . and ferocious in the extreme.” Frequently away supervising the trade, he usually accompanied the pelt returns to the Columbia River in the fall. To economize on imported foodstuffs, Work established a garden at Fort Simpson, and in 1839 he assisted in surveying Cowlitz Farm for the Puget Sound Agricultural Company, a subsidiary of the HBC supplying provisions to the Russians at Sitka (Alaska).

Although Work had often expressed his desire to find “a corner of the Civilized World in quietness,” concern for the cultural duality of his family led him to settle permanently at Fort Victoria (he had married Josette Legacé, a Spokane woman of mixed blood). In August 1852 he purchased 823 acres of farmland on the northern outskirts of Victoria and built a mansion, Hillside. By 1859, he owned over 1800 acres, the largest land holder on Vancouver Island.

Comfortably perched in the comfy banquette in the pilot house, I’ve been distracted by historical research into the men who attempted to tame this wilderness and realize it’s getting dark. Chris needs my help readying the fenders as we approach Cone Island which protects the tricky entrance to Klemtu. The island derives its name from Bell Peak, a conical mountain also known as “China Hat” after hats worn by early Chinese immigrants who worked in the canneries and mines here.

Klemtu is a tiny village on Trout Bay; the few slips at the marina are already full. We’ll need to anchor, and Chris carefully consults the charts to ensure situating the yacht so we won’t be high and dry when the tide changes. A delicate maneuver to set the forward and aft anchors after which we shut down the engines, turn off the running lights, and switch on our anchor light.

The water is an inky glass mirror, a million stars dust the sky, and we float only a few hundred yards from the Klemtu Longhouse on the rocky promontory. As we sit outside on the flybridge, enjoying a light supper and glass of wine, I can easily imagine this quiet cove rimmed with the totem poles and longhouses of hundreds of years ago.

© Copyright 2012-2026. Lisa Scattaregia. All rights reserved.

You must be logged in to post a comment.