The hum of our generator wakes me. I can hear Chris making coffee and he’s already pulled in our shore power cord and the two spring lines. I climb down from the snug bed in the forward V-berth and pull on a turtleneck, pair of leggings and fleece sweatshirt. It’s still pitch black, but our last leg in this amazing journey will take twelve hours or more so he’s getting the boat ready to leave just before first light. Dew still clings to our deck and windows, so I grab a cup of coffee and head up to the pilot house.

Although a frequent stop for refueling and provisions for small boats and fisherman, Bella Bella remains a frontier town. In 1876, a Canadian reporter for the Toronto Globe described the settlement at Bella Bella: “The Indian houses situated on the very edge of the water were built of roughly hewn cedar planks about 15 or 18 feet square. The planks are made by splitting cedars which have grown to an enormous size and smoothing them after a fashion. Posts are stuck in the ground and the planks are nailed around them. A plank bark covered roof is then put on with an aperture in the centre for the escape of smoke. Round the enclosure in several different corners were small rooms which were doubtless the dormitories of the commingled families. In the centre of the main floor a fire smoldered, over its smoke hung lines of dried salmon and other fish, together with berries, skins, bark or any other article of household use that required drying or seasoning. Round the common chamber, squatting on the packed mud floor, were women smoking their pipes and busily engaged in making baskets and mats. They seemed quite content to be visited and the elderly ones made light and amusing jests at our expense. In every house, there was at least one slumbering papoose and an endless variety of dogs. There was a very ancient and fish-like smell about these dwellings…”

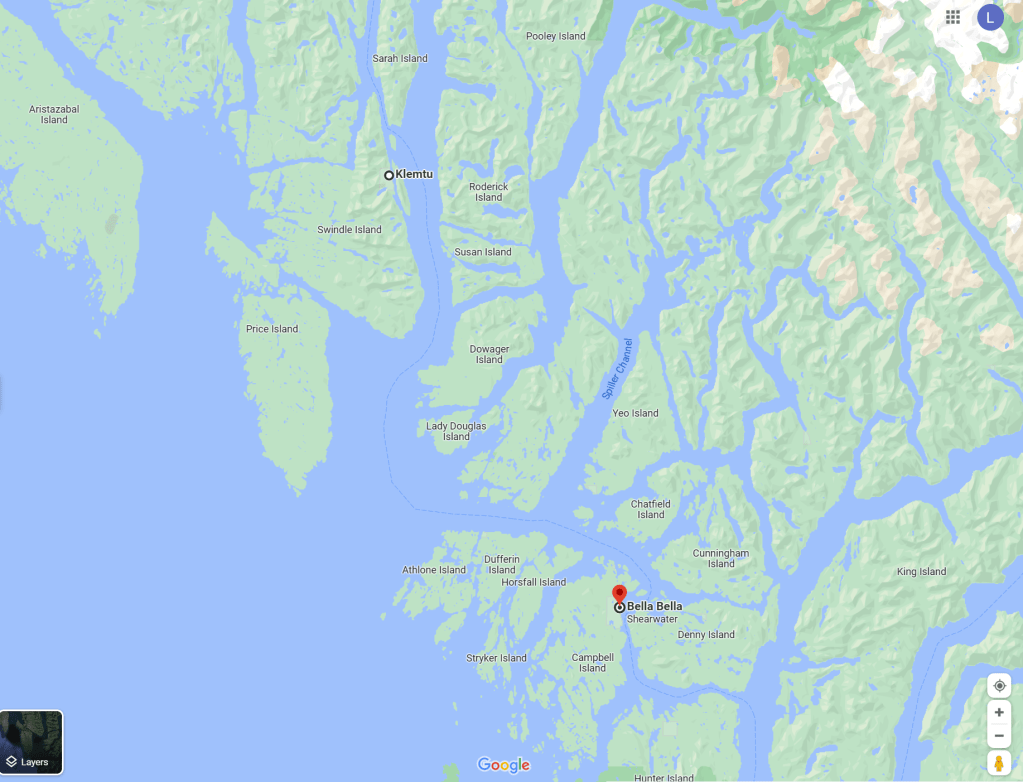

As we leave civilization behind, the water is a gray silk mirror. We thread the narrow channel between Denny Island and Campbell Island, then skirt the north side of Hunter Island. Sailing down its eastern shore, the channel widens along Nalu Island and Hecate Island. The fog and rain only add to the beauty of this place.

In 1987, British Columbia established the Hakai Protection Area to safeguard the marine and wildlife in the Hunter Islands archipelago, as well as the beautiful, long, sandy beaches on Calvert Island. Orca, humpback and grey whales, porpoises, dolphins, sea lions and river otters flourish here. The intertidal zone hosts a wide variety of mollusks, crabs, starfish, anemones, and sea urchins. On the islands of the Hakai, you’ll find black bears, wolves, black-tailed deer, and mink. Chinook, Coho, Sockeye, Chum and Pink salmon all swim through here on their way back to mainland rivers and streams. Halibut, lingcod and rock cod are common. More than 100 species of birds have been spotted in this rich environment: bald eagles, kingfishers, osprey, cormorants, sandpipers, loons, gulls, auklets, murrelets, oystercatchers, even black and ruddy turnstones.

Here we enter Fitz Hugh Sound where the ghost town of Namu lies to our west. At one time, Namu had a population of 400 cannery workers, office personnel and their families. The cannery was started in 1893, followed by a sawmill in 1909 to provide lumber for the cases of salmon. As with most canneries at the turn of the century, labor, working hours and housing were segregated into groups of First Nation natives, Japanese, Chinese, and Caucasians. The British Columbia Packers Ltd, the largest fishing and fish processing company in B.C., took over operations in 1928. By 1970, structures included several two-story bunkhouses, dozens of family cottages, recreation and mess halls, along with the fish processing facilities, an electric power plant, and a large pier—all connected by a maze of boardwalks.

In the 1990s, declining fish stocks and improved refrigeration on fishing boats eventually forced BC Packers Inc. to sell the facility. Purchased by a developer with plans to build a sportfishing resort, the idea was later abandoned. Many of the original buildings were torn down or lost to fires; however, the large fish processing facility, pier and a few homes that remain are slowly rotting away. There are dozens of these abandoned canneries along the Inside Passage—something that makes the daily bounty of fresh frozen fish displayed in the glass case at my local grocery store seem all the more miraculous.

The water is an evergreen color this morning and a row of sea gulls on a floating log looks more like an impressionist’s painting.

Queen Charlotte Strait between Vancouver Island and the mainland of British Columbia connects Queen Charlotte Sound with Johnstone Strait to Discovery Passage, the Strait of Georgia and eventually Puget Sound—an important link in the Inside Passage from Seattle to Alaska used by the men who sought their fortunes in the Klondike gold fields a century ago.

The swells are gentle as we enter the open water of Queen Charlotte Sound and we use binoculars to view a few whale spouts in the distance – most likely Orca whales off to their favorite hunting grounds for seals in the Queen Charlotte Islands offshore.

I photograph a family of playful sea otters in the kelp beds, but we are both surprised not to spy more wildlife this afternoon.

As we enter Johnstone Strait at the northern most tip of Vancouver Island, miraculously the clouds and fog begin to lift.

An hour later, we pass a BC Ferry bound for Port Hardy. Port McNeill, sheltered by Malcolm Island, was originally a base camp for loggers and didn’t become a settlement until 1936. Not surprisingly, another town named after a Captain in the Hudson Bay Company (William McNeill).

A barren sandspit on the southwest corner of Malcolm Island, Pulteney Point marks the separation of Broughton and Queen Charlotte Straits. Named in 1846 after Admiral Sir Pulteney Malcom, a Scottish-born British Naval Officer, famous for chasing the French fleet all the way to the West Indies following the Battle of Gibraltar. Kwakiutl legends say the island rose up from the water and someday it would return to its watery grave. For this reason, the natives never inhabited the island although they did harvest cedar for ceremonial masks and totem poles.

In 1900, a group of Finnish immigrant coal miners in Nanaimo petitioned Canada for a piece of land to escape their miserable working conditions and create a Utopian community. They were given Malcom Island. Sointula—the Finnish name of the island’s main town—means “a place of harmony.” The Finns petitioned for a lighthouse to be built at Pulteney Point in 1905 and their descendants served as lightkeepers for the next 100 years. In 1942, the nearby Estevan Lighthouse was shelled by the Japanese, and all lights along the West Coast were ordered to “go dark.” With no light to guide her, the Alaska Steamship Company’s Columbia ran aground on the spit.

In June 1792, dealing with poor weather and dwindling food supplies near here, Captain Vancouver encountered the Spanish ships Sutil and Mexicana under the respective commands of Captain Galiano and Valdes. Both were exploring and mapping the Strait of Georgia, seeking a possible Northwest Passage and were also trying to determine if Vancouver Island was in fact an island or part of the mainland. The two commanders agreed to assist one another by dividing up the surveying work and sharing charts. Working together until early July, they then split up: the British ships circumnavigating the island starting in the Strait of Juan de Fuca and navigating east and north, while the Spanish ships started in Nootka on the West Coast navigating west and north.

On July 19, 1792, Captain Vancouver traded sheet copper and blue cloth for sea otter skins at Nimpkish, just south of present-day Port McNeill. Lieutenant Broughton wrote, “In the afternoon, I went with Capt. Vancouver and some of the officers accompanied by the Chief to the Village. We found it pleasantly situated, exposed to a Southern aspect, on the sloping bank of a small creek well sheltered behind a dense forest of tall pines. The houses were regularly arranged and from the Creek made a picturesque appearance by the various rude paintings with which fronts were adorned. On our approach to the landing place in the two boats, several of the natives assembled on the beach to receive us and conducted us very orderly through every part of the village. We observed the houses were built very much in the same manner as Nootka, but much neater and the Inhabitants being of the same Nation differed very little either in their manners or dress from the Nootka tribe. Several families lived in common under the same roof, but each had their sleeping place divided off and screened in with great decency and a degree of privacy not attended to in the Nootka inhabitations. The Women were variously employed, some in culinary occupations, others were engaged in Manufacturing of Garments, Mats and small Baskets and they did not fail to dun us for presents in every House we came to in a manner which convinced us they were not unaccustomed to such Visitants. Buttons, Beads and other Trinkets were distributed amongst them and so eagerly solicitous were they for these little articles of ornament that our pockets were soon emptied of them & tho they were free & unreserved in their manners & conversation, yet none of them would suffer any of our people to offer them any indecent familiarities, which is a modesty of some measure characteristic of their Tribe. On coming to an elderly Chief’s House we were entertained with a song which was by no means unharmonious, the whole group at intervals joind in it & kept time by beating against planks or any thing near them with the greatest regularity, after which the old Chief presented each of us with a slip of Sea Otter Skin and sufferd us to depart.”

Perhaps fitting the Broughton Archipelago Marine Park, established in 1992, was named after this Lieutenant who so vividly described early explorations 220 years earlier. The Park lies east of Malcolm Island and is British Columbia’s largest marine park with dozens of undeveloped islands, sheltered waters, and peaceful anchorages framed by tall peaks of the coastal mountain range to the east. A mecca for sea kayakers from around the world, I can’t help but wonder what Lieutenant Broughton would write about this wilderness today.

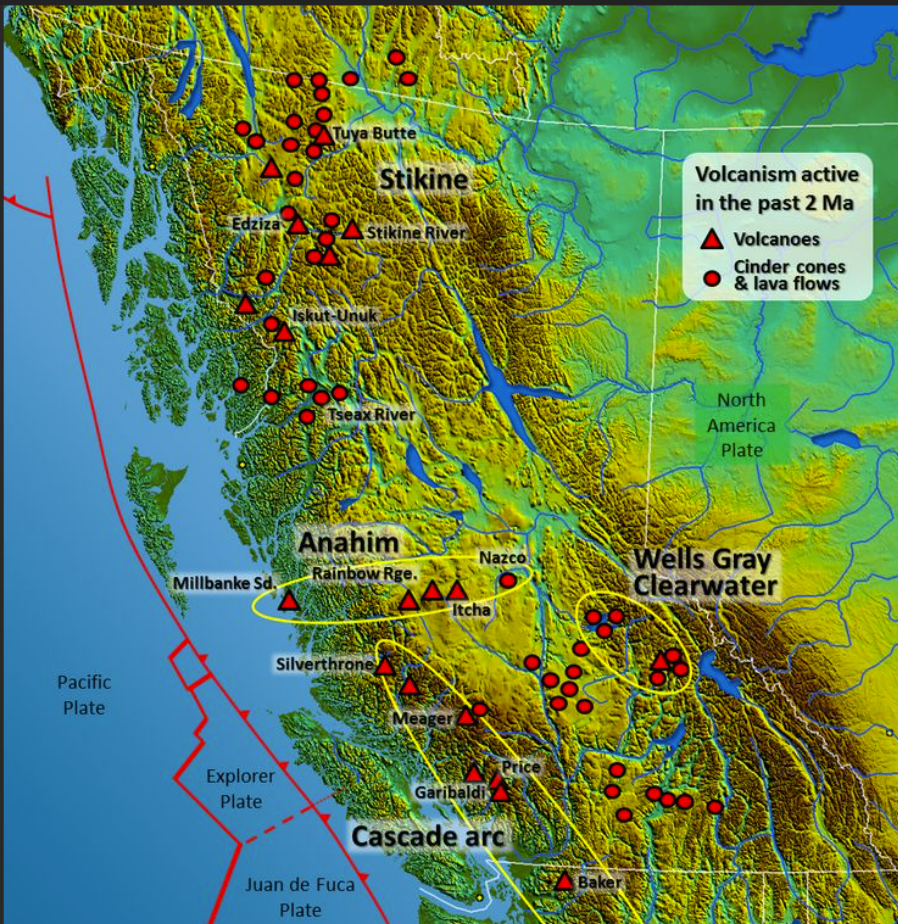

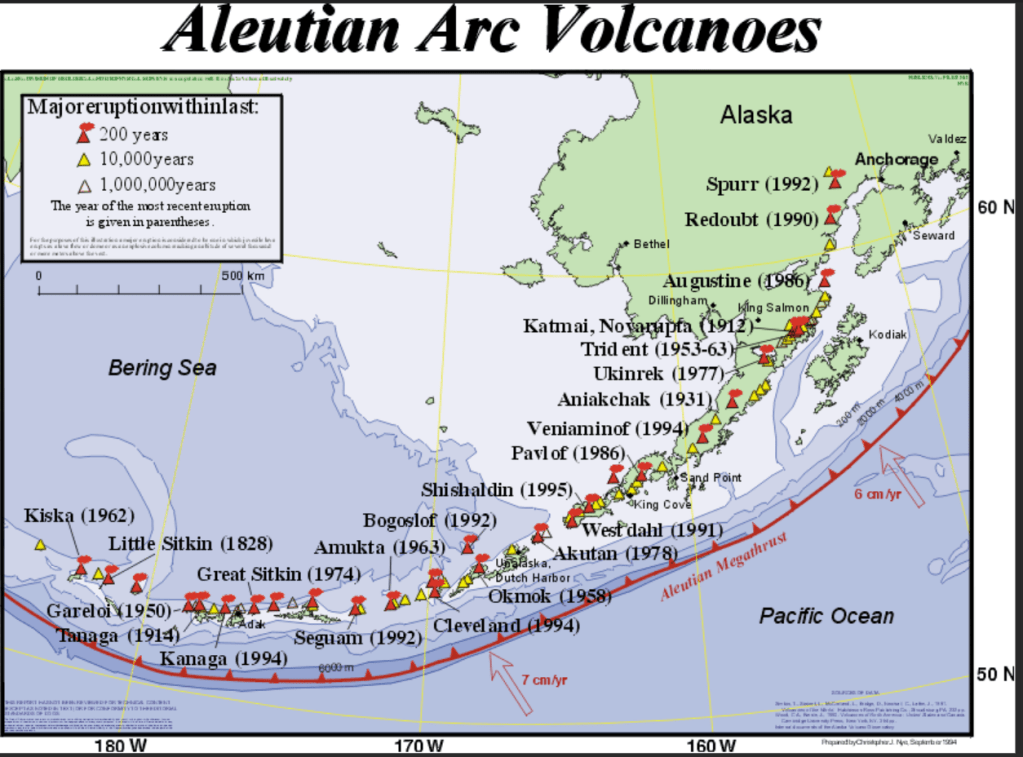

As we swing around Ledge Point to the marina, tiny Haddington Island, a mere 98 acres, is directly off our bow. Formed more than 3.7 million years ago as the Juan de Fuca plate to the west, subducted under the North American Plate, the island’s blue-grey to buff-colored andesite rock, prized for stone carving and sculpture, can be found on some of the province’s most famous buildings: The Empress Hotel and Parliament buildings in Victoria and the Vancouver Art Gallery, Hotel Vancouver and Vancouver City Hall.

As it’s the height of summer, the docks are crowded with all sizes of pleasure boats, yachts, even tall-masted schooners. Our berth is a tight squeeze between two other boats. After tying up for the night, we enjoy fresh Halibut fish & chips at the local pub.

The marina is magical as dusk deepens to night and boat lights reflect on the water. On our last night aboard, I also reflect on our remarkable journey. We were always connected to civilization by radio and GPS, never too far from a friendly port to stock up on provisions, a safe harbor or anchorage for the night easily identified on our nautical charts.

Yet with all these advantages today, boats still sink or run aground. I can’t help but wonder about the early explorers of these vast—and then largely uncharted—waters. The men whose writings I have read and quoted in this blog. Their primitive wooden ships. Their meager supplies dependent on successful fishing or hunting for food on the islands. Their families not hearing from them for years at a time. Those who did not survive.

My friends think I am brave to sail the Inside Passage in a relatively small boat. Adventurous maybe. But “brave” is a word that belongs to those early sailors.

© Copyright 2012-2026. Lisa Scattaregia. All rights reserved.

You must be logged in to post a comment.