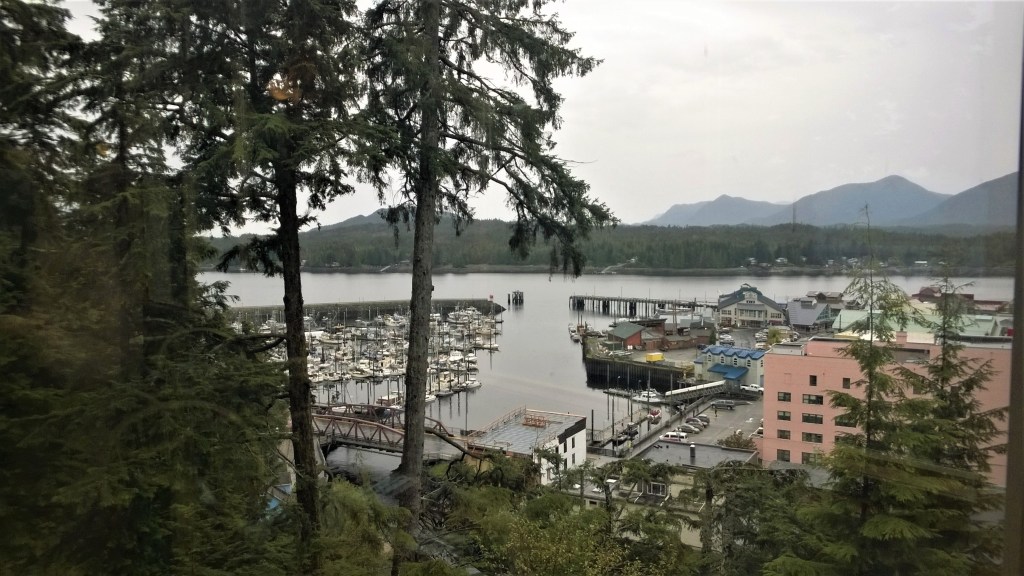

We are underway at 4:52 am, the streetlights of Ketchikan still shining in the morning twilight. Sailing south in Tongass Narrows, we will pass Saxman Village, the largest collection of totem poles in the world. Chilkoot Tlingit and Haida artisans still carve totem poles out of carefully selected Western Red Cedar logs.

First noticed by European explorers in the 1700s, totem poles were misunderstood. Captain James Cook, who saw totem poles off the coast of British Columbia near Tofino, called them “truly monstrous figures.” Even today, when someone refers to the “low man on the totem pole” they may not realize that the bottom figure was usually the most important one – and it was not a man. It might have been the orca, raven or salmon.

Early totem poles were billboards for rich and powerful native families, telling stories about the family and the rights and privileges they enjoyed. With early traders came more wealth, and more poles, some 19th-century native villages had hundreds of totem poles, each one shouting out the power and wealth of the family behind it. Early missionaries thought the totem poles were worshiped as gods and encouraged them to be burned.

Before iron and steel arrived in the area, natives used crude tools made of stone, shells, or beaver teeth for carving. The process was slow and laborious; axes were unknown. By the late eighteenth century, the use of metal cutting tools enabled more complex carvings and increased production of totem poles. The tall, monumental poles in front of native homes in coastal villages probably did not appear until the early 1800s.

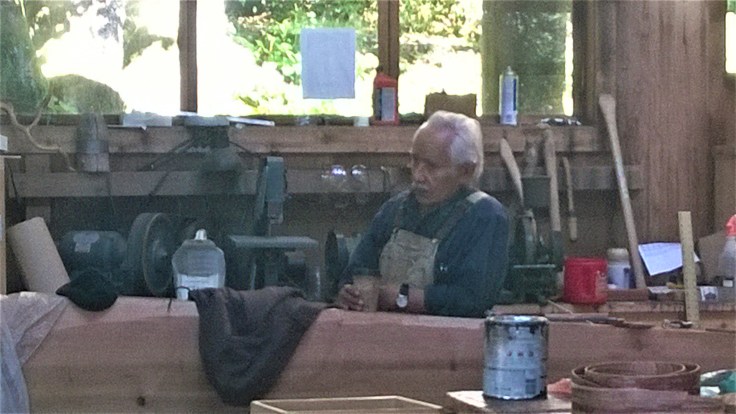

A highlight on one of my earlier visits to Ketchikan, I had watched the white-haired and revered carver Nathan Jackson at work on a ceremonial canoe in the Carving Shed, a small woodshop on the site. Just outside the shed, the choicest cedar logs are marked with initials “NJ” waiting for him to transform them into stunning works of art.

In the 19th century, Tongass Village was famous for the dozens of giant totem poles standing guard in front of longhouses. Prospectors from the gold fields reported finding a totem pole with an actual telescope attached to the top bearing the inscription “James Cook 1778.” Village elders explained the telescope had been a treasured gift from a white man to their fathers. In 1899, the Seattle Chamber of Commerce and the Seattle Post Intelligencer sponsored a tour of Alaska aboard the sloop City of Seattle. They removed one of the giant totem poles from the deserted Tongass Village, sawing it in half in order to get it on board. After it was erected in Pioneer Square, the Tongass villagers claimed theft and demanded its immediate return. Eventually, the city paid for the pole, and it was allowed to remain in Seattle.

We skirt Race Point and head toward Spire Island Reef, where the famous gold ship Portland went aground on the evening of December 20, 1905. More than 100 years later, it is easy to forget it was the Alaska Gold Rush that put Ketchikan—and also Seattle—on the map.

The white hulk of the Norwegian Splendor, a symbol of the modern gold rush, rumbles into view as she approaches the Tongass Narrows bound for Ketchikan. Tourists are already on the bow and flashes from their cellphone cameras flicker like fireflies. Our radio crackles with a woman’s voice alerting us “. . .pleasure vessel Well Sea approaching to pass . . .” and she also signals the tug pulling a large barge a few hundred yards behind us. They intend to pass us both port-to-port in the narrow channel. I smile. Only officers are permitted on the Bridge during Red Manning (nautical protocol when a ship is coming into port) so the woman’s voice is a rarity in the cruise industry—a female Senior Officer on the Bridge.

I study our chart book, Skagway to Barkley Sound, and realize the people onboard this cruise ship will not see any of what we will today. Their ship has run all night while they slept, they will disembark for a few hours in Ketchikan, and then the ship will run again all night to the next port. A similar timetable repeated by nearly all the cruise companies.

Speaking of maps, while Vancouver seemed to name everything after men of the era or men on his ship, gender equality seems to exist at least in this corner of the wilderness. We are passing Annette Island to starboard, named by William Dall for his wife in 1879. Admiral Winslow who cruised past here while on board the U.S.S. Saranac in 1872 named the sweet little island to our port after his daughter Mary. Helen Todd Lake was named for a woman pilot from Ketchikan who was killed when her plane crashed here in 1965.

Point Alava, which Vancouver named after the Spanish governor (no surprise another man), is where we head south into Revillagigedo Channel, named by the Spanish explorer Camano after Juan Vicente de Guemes, the 2nd Count of Revillagigedo and Viceroy of New Spain in 1793. A vast area, New Spain included what is now the West and Southwest U.S. from California to Louisiana to Florida, parts of Wyoming, as well as Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, and the Pacific Coast to Alaska.

The chart of Cape Northumberland, an area noted for extreme magnetic disturbance, notes many plane crashes in the area including a Pan Am DC-4 which crashed on Tongass Mountain in 1947 killing all 18 people.

In the narrows, a tug calls us on the radio advising he would like to overtake us on our port. “Roger that,” replies my friend as he slows to six knots to give the tug and barge a wide berth. Many people in the continental U.S. are unaware that the west coast of Alaska and British Columbia is actually a vast archipelago, more than a thousand islands spanning thousands of miles. Tugs towing barges ply these watery highways delivering everything from building materials to appliances to new cars. Ferries and float planes are the other principal modes of transportation to many of the small, isolated communities on these islands.

We skirt Tongass Island, the site of Fort Tongass established soon after the United States purchased Alaska from Russia. In the summer of 1868, it was a small tent encampment with 60 men.

The historic notes on our charts indicate there were once fox farms on the nearby islands during the 1920s when fox furs with heads and tails still attached were in fashion in Chicago and New York. There were also quarries for slate, marble and limestone, as well as gold and copper mines; however, most notations on these islands reference canneries, fisheries, and packing houses.

I’m fascinated by the fact that Dickens Point was named after Lieutenant Sydney Smith Haldimand Dickens, the fifth son of Charles Dickens, the great novelist of the Victorian era. Dickens who had 10 children created those memorable characters in books we all studied in high school: Oliver Twist, David Copperfield, Great Expectations and The Tale of Two Cities. Sydney, who Dickens called a “born little sailor,” joined the Royal Navy at age 14 as a cadet on the HMS Britannia. Sydney was just 22 when sailed these waters in 1868. Reportedly an actor of some talent, his role in a theatrical performance in Victoria that same year was the inspiration for Captain Pender naming the rocky outcropping after the young Lieutenant. While Charles Dickens is buried in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey, his young son died on a passage home from India to England and was buried at sea in the Indian Ocean. He was just 26 years old, had never married, and had no children. But he had explored this corner of the world when these waters were still brimming with sea otters, hundreds of whales, and 75-pound King salmon.

As we enter Chatham Sound, there are clusters of small islands in all directions but it’s starting to rain obscuring the details in a silvery gray mist. I curl up for a nap on the bench in the pilot house, the hum of our engines lulling me to sleep.

I wake as we pass Digby Island and start our approach to Prince Rupert. The name of this busy port was selected by an open competition by the Grand Trunk Pacific Railroad with a prize of $250–a large sum in those days. More than 12,000 people submitted ideas that met the criteria: the name could not be more than 10 letters and not more than three syllables. Two people submitted “Port Rupert” and Miss Eleanor MacDonald of Winnepeg submitted “Prince Rupert” after the illustrious soldier and explorer (the only person to submit his name). In the spirit of fairness, the Committee decided to award $250 to all three.

Our overnight anchorage is a picturesque marina where I spend a pleasant hour watching fisherman clean salmon and feed the tailings to a friendly family of harbor seals. With each passing mile today, time moves more slowly, and the modern world is further away.

© Copyright 2012-2026. Lisa Scattaregia. All rights reserved.

You must be logged in to post a comment.