A minus tide has exposed a wide swath of rocky beach where juvenile eagles scavenge clams and crabs in the early morning light.

Thankfully, our late-night anchoring held firm and we are still floating in a shy fifteen feet of water. If we had anchored closer to shore, our stern would be stuck in the mud. Chris’ careful reading of the chart and mindful calculations of the tide have kept the Well Sea well situated.

A slight mist is lifting, and the black and red talismans painted on the Klemtu Longhouse are now distinct. The Kitasoo and Xai’xais are two of the fifteen Tsimshian nations that call the Great Bear Rainforest home. Thousands of years ago, the Kitasoo people lived in villages scattered along rivers, bays and inlets of the outer central coast. The Xai’xais settled in the large river systems on the mainland of the central coast. They were not nomadic tribes due to the abundance of natural resources and plentiful marine life.

According to tribal legends, Raven made one in every ten black bears white to remind the people of a time when glaciers covered the world so they would become thankful stewards of the bountiful land. For many years, tribal elders rarely spoke of the legendary and elusive Spirit Bear for fear it would be hunted into extinction if word spread of its existence. Yet today the opposite has happened: tourists from across the globe travel to Spirit Bear Lodge in Klemtu for a chance to glimpse the rare and endangered Kermode Bear in its natural habitat (it’s estimated that only 50 to 100 of these white bears exist).

Around 1875, the two tribes began to settle in Klemtu (a word meaning “blocked passage”) to take advantage of its strategic location for trade and to supply cordwood to steamships traveling the Inside Passage. In the 1830s, exposed to viruses from the colonialists, the Kitasoo and Xai’xais villages suffered devastating losses. When the Canadian government established the reserve system and moved remaining “Indians” in the territory to Klemtu, the two distinct tribes formed one First Nation.

The natural ecosystems in the region also suffered from colonialism. For more than 100 years, resources such as fish and forests, were unsustainably extracted with no compensation provided to the Kitasoo/Xai’xais people. Klemtu, like other First Nation communities along the coast, suffered extensive economic, social, and cultural damage throughout this period.

Starting in the 1980s, the tribes began developing a community-based economy. Using revenue from a commercial herring spawn on their kelp license and securing additional community-owned licenses for sea cucumbers, urchin, prawns and other marine life, they were able to build a seafood processing plant. Next, they began farming salmon which provided significant new revenues and jobs. Eventually, management over forest harvesting in the territory led to acquisition of forest tenures and additional revenues.

Today, Spirit Bear Lodge is a worldwide model of conservation-focused ecotourism that minimizes impact on the land and animals in this remote corner of Canada. Recognized as a best practice model for Indigenous community-based tourism, the revenues from the Lodge support the protection of the Kitasoo/Xai’xais culture, language, and traditions. As the Lodge grew it helped the Nation play a much bigger role in stewardship and management of their territory. Ecotourism activities at Spirit Bear Lodge are aligned with Kitasoo/Xai’xais cultural values. “The elders always say what we have is not ours, we’re just holding it for the next generation.”

Our next segment is a short run this morning, so we linger here in Klemtu while I bake a batch of cinnamon rolls and fix a leisurely breakfast of fried Italian Coppa ham and scrambled eggs with capers and feta cheese.

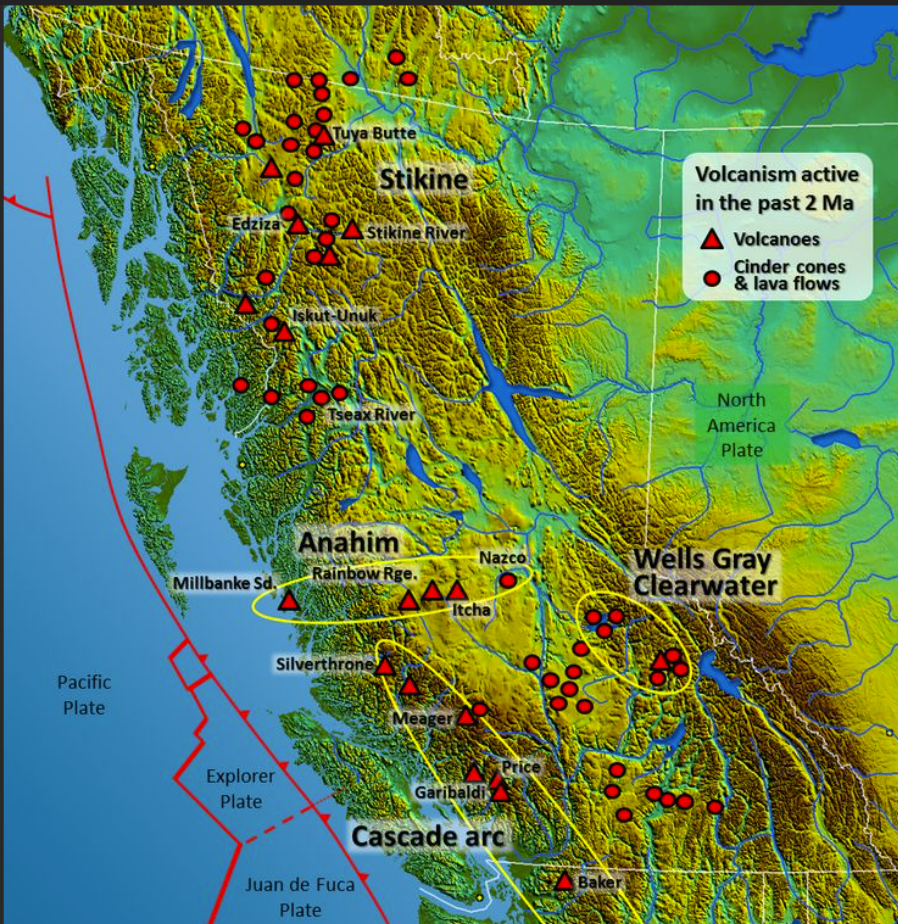

After retracting and hosing off our muddy anchors, we are underway. I pull in the fenders as we round the promontory of the Longhouse and slip into peaceful Tolmie Channel. Cone Island shelters Trout Bay—Klemtu actually sits on Swindle Island, part of the volcanic cluster called the Milbanke Sound Group. Kitasu Hill on the Pacific side of the island is a monogenetic basalt cinder cone that produced lava flows thousands of years ago. A monogenetic volcanic field consists of volcanoes which erupt only once, as opposed to polygenetic volcanoes which erupt repeatedly over a period of time. Monogenetic volcanoes occur where the supply of magma is low or where vents are not close enough to the surface or large enough to develop systems for continuous feeding of magma.

Part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, the western mountain ranges in California, Oregon, Washington, British Columbia are home to more than 100 polygenetic volcanoes including Mount Baker, Mount Rainer, Mount St. Helens, Mount Adams, Mount Hood, Mount Bachelor, Mount Jefferson, Mount McLoughlin, Mount Shasta, and Mount Lassen. Make no mistake, while many are dormant, these are still active volcanoes—Lassen erupted violently in 1917 and Mount St. Helens stunned the world in 1980.

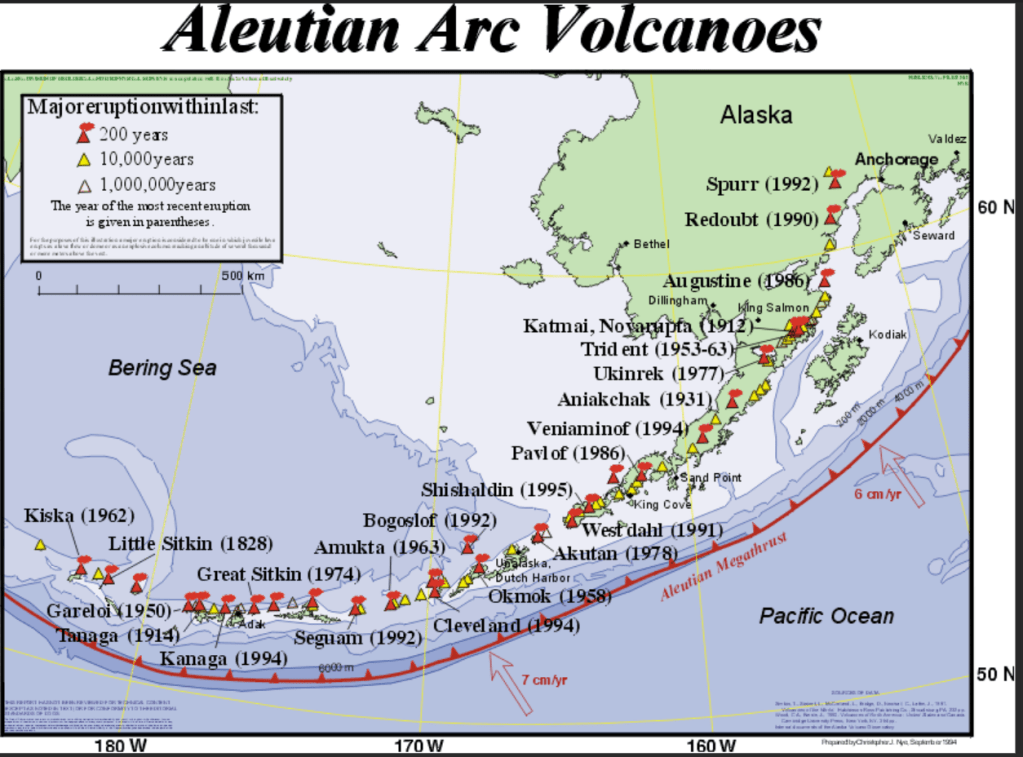

There are more than 130 volcanoes in Alaska and dozens have erupted in the last 100 years. Mounts Shishaldin on Umimak Island, a picturesque volcano, symmetrical and smooth like Mount Fuji in Japan, erupted in 2020. The tallest mountain peak in the Aleutian chain of islands rising over 9000-feet above sea level, its upper portion is covered year-round in glacial snow and ice, and a thin stream of smoke continually rises from the crater. At over 10,000 feet high, major eruptions of the imposing Mount Redoubt, just west of Cook Inlet, grounded jetliners in Anchorage for days (1989 and 2009).

Sailing south through Tolmie Channel, we pass by Star Island, Needle Rock and Fish Island. Like the water in Trout Bay, this channel is relatively shallow (between 32 and 80 feet) but as we merge with the wider Finlayson Channel our depth gauge shows the ocean bottom drops off quickly to an average 2000 to 3200 feet of water. Named after Roderick Finlayson, a Scotsman with the Hudson Bay Company who is considered the founder of Victoria, this channel is a major highway of the Inside Passage. This morning we are the only boat in any direction.

I have to smile when consulting our chart—a few more places with female names. We’ll be skirting Susan Island, Dowager Island, Suzette Bay, and Lady Douglas Island. To starboard sits Mount Sarah on Swindle Island while Mount Jane crests Dowager Island at 2372 feet. There’s also Squaw Island, although its name might not pass muster today as politically correct.

Finlayson Channel empties into Milbanke Sound and here we encounter larger swells that have rolled in from Queen Charlotte Sound to the west. To our east, the Fjordland Conservancy preserves a portion of these glacial fjords. Established in 1987, the park covers 189,838 acres and was the first on the North American continent to protect this type of environmental zone. Since there are no roads, the Park is mainly enjoyed by kayakers and sailors.

Chris is hoping we might sight whales in Milbanke Sound, named after Vice Admiral Mark Milbanke who commanded the British fleet at the Battle of Gibraltar in 1782. Certainly, there were abundant whales here when Vancouver and Cook explored these waters. Today, we spot only a few Dall’s porpoises, a common species in the northern Pacific, often mistaken for Orca whales. Dall’s porpoises have a wide hefty body, a comparatively tiny head, no distinguished beak and a small, triangular dorsal fin. Mostly black with white to grey patches on the flank and belly, they are the largest porpoise species, growing up to 7.5 feet in length and weighing between 370 and 490 pounds.

Our crossing of Milbanke Sound passes quickly and soon we spot the Ivory Island Lighthouse which marks the entrance to Seaforth Channel, our final “turn” enroute to Bella Bella. Constructed in 1898 on an exposed rock, this lighthouse has endured many brutal storms, tidal waves, and tsunamis. But perhaps the most romantic story belongs to Gordon Schweers who became the head lighthouse keeper in 1981. He and Judy corresponded for nine months, before she left her family in California and headed north to marry a man she had never met and start a new life on this remote island. The kind of adventure story one might normally attribute to a woman in the 1880s, not the 1980s.

The first year on Ivory Island would test the couple’s mettle. On Christmas Eve 1982, nearby McInnes Island Lighthouse reported their barometer was 29.88 and falling rapidly. A winter storm had been buffeting the lighthouse station for about a week, and now the weather was getting worse.

Gordon and Judy were living in the main building which had been carefully built with seasoned fir and reinforced floors. Gordon reported that night “it was groaning in every rafter like an old barque” as gale force winds swept along the open ocean from Cape St. James to the station’s back door. The combination of wind and water made the kitchen windows “resemble a plastic sheet which was expanding under heat.”

The tide peaked early on Christmas morning when a wave surmounted the sea wall and flooded the station. Gordon later wrote the following description of that memorable Christmas Day:

“Our only indication that we were ‘over our heads’ came when the outer door to the radio room filled entirely with white sea water. For a second the door seemed to resist – then the dam burst, flooding sea water and debris into the kitchen pantry, basement, living room and cistern. Neither keeper was injured by flying glass, even though I had bare feet and fled the room while it was still awash. Andrew [the radio operator] followed abruptly, since the same wave in uprooting small trees and severing larger limbs had stripped the radio room roof bare of shingles. With an outer kitchen window shattered, we moved back into the safety of another room, but were again interrupted while ebbing the flow of water. There is no way of knowing whether the 32-foot metal tower was knocked down by the same wave or one succeeding it, yet the DCB 10 main light shone [its] search beam hard through the living room windows for several minutes before burning out. In the confusion I had briefly mistaken it to be the beam from a ship driven off course by the storm.”

Besides the dwelling, only the station’s radio antenna, braced by eight guide wires at the southeast corner of the point, remained standing. As adventuresome as I am, I doubt I would have stayed on this barren rock connected by only a footbridge to civilization on the adjacent Lady Dowager Island.

The importance of Ivory Island Lighthouse is evidenced by the fact it remains staffed today despite its dangerously exposed location.

As we round the bend in Seaforth Channel, we are in the Lady Douglas-Don Peninsula Conservancy, comprising several coastal islands and an intricate mainland shoreline with numerous small bays, coves, passages and shoals. This conservancy protects the important Marbled Murrelet habitat. The Marbled Murrelet is a small North Pacific seabird and a member of the Auk family. While suspected of nesting in old-growth forests, it was not documented until 1974 when a tree-climber found a young chick in a nest, making it one of the last North American bird species to have its nest described. The Marbled Murrelet has declined in significant numbers since humans began widespread logging of its nest trees in the 1850s. Considered globally endangered, the bird has become a bellwether for the forest preservation movement.

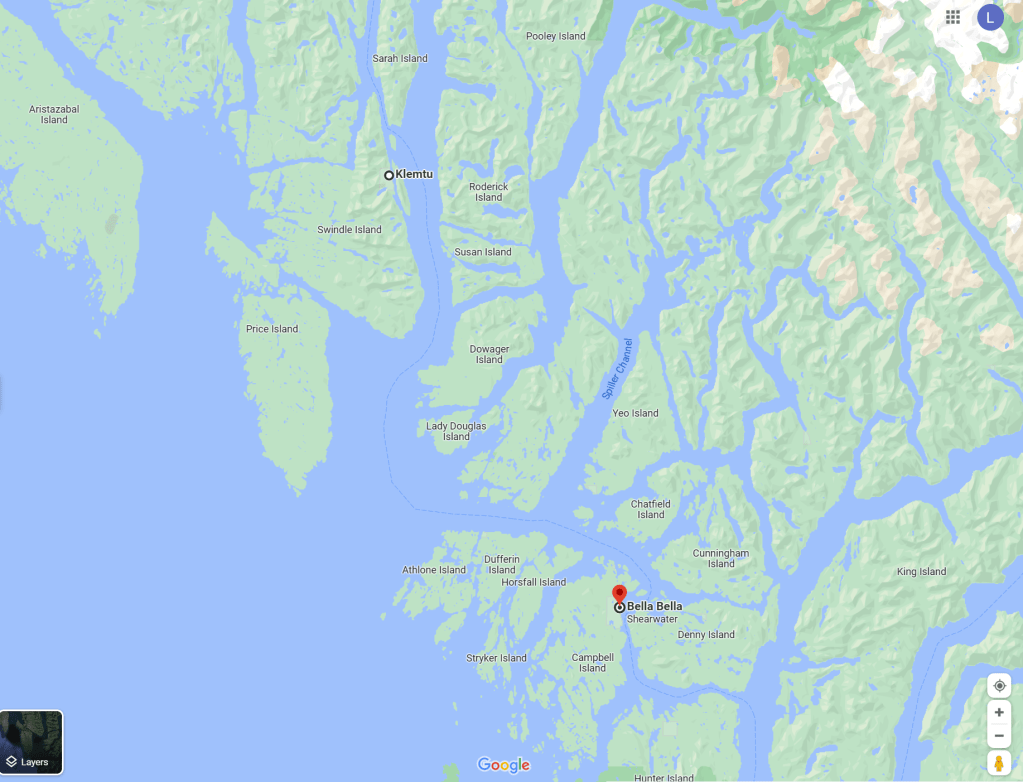

We keep to the center channel as we pass Dearth Island and dozens of small islets where underwater rocks are a navigation hazard. The beacon on Dryad Point marks our turn into the narrow entry to Bella Bella between Campbell Island and Saunders Island. Our depth gauge shows we go from 300 to 400 feet of water to 80 feet or less in a just a few hundred yards.

As we enter the Shear Water Marina, dozens of weathered commercial fishing boats with their distinctive winches and buoys line every dock. Commercial and recreational fishing in British Columbia is fiercely regulated: there are certain “Open Seasons” for different fish, daily limits, possession limits, and annual limits. The type of gear used is also specified. For example, fisherman can only use barbless hooks and lines for all varieties salmon; dip nets, ring nets and specific traps for crab; hook and line for halibut, sablefish and cod; and herring jigs, herring rakes, dip nets or cast nets for herring, sardines, anchovies, and mackerel.

While it’s starting to rain, Chris wants to fill up at the fuel dock before we tie up for the evening since we have a very long run tomorrow. Once snuggly in our slip at the dock, I take pictures of the majestic eagle standing guard on a nearby snag.

I savor this luxury of time where I can spend the evening reading in the enclosed pilot house while listening to rain on the roof.

© Copyright 2012-2026. Lisa Scattaregia. All rights reserved.

You must be logged in to post a comment.